Honeyguides: Uniting People and Honey in Mozambique

August 08, 2016

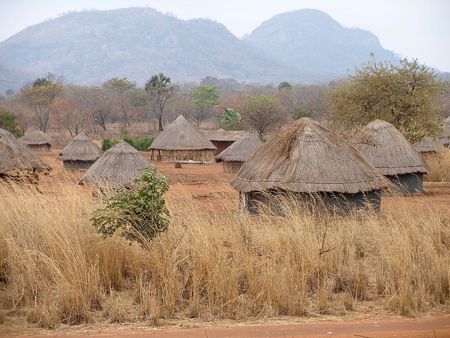

Most have heard that within nature, animals can form symbiotic relationships with other animals, plant life, and so forth, with some being commensal, mutualistic, or parasitic. In northern Mozambique, a southern African country across the channel from Madagascar, the village of Mbamba and its surrounding plains is the home to a mutualistic relationship many believed couldn’t exist—that of humans and the wild birds, greater honeyguides. For centuries, the Yao men of Mbamba have relied on honeyguides to help find and forage honey. Small enough to fit inside a shoe, adult females are brown and gray while males have pink beaks and golden feathers throughout their wings (a pattern also seen in peacocks and cardinals). More importantly, honeyguides love finding beeswax—from there, people and honeyguides found a mutually successfully arrangement.

Honeyguides know where local bees’ nests are but cannot reach them, whereas the Yao have no trouble harvesting nests but cannot find them since they’re often tucked into burrows or inside rotting tree trunks. To begin the process, the birds are summoned with a unique call—“Brrr-hm!”—and the birds respond, leading the men to nests. The Yao collect honey and take it home to eat or store it to sell, with the honeyguides eating leftover wax. According to a paper in the journal Science, no other wild animal has been shown to collaborate with humans so directly and successfully.

Lead author Claire Spottiswoode, a behavioral ecologist at the University of Cambridge who studied honeyguides in Zambia, had never witnessed this cooperative behavior between people and honeyguides, but upon coming to Mbamba, she quickly realized it was a common sight in that area. “This was enormously exciting for me—electrifying,” Claire recalled. “Finally, a place to study the honeyguide-human relationship!” Claire’s fieldwork included trailing Yao honey-hunters, and she found that whenever honeyguides could be recruited, the hunters encountered nests more than 75 percent of the time. Seventy-two simulations showed that of the different sounds the researchers used, it was the “Brrr-hm!” sound that tripled the probability of finding bee nests. “Rather uncanny,” as Claire stated.

The magnificent thing about the discovery of this old practice is while animals have always been used by people for hunting, those animals are usually domesticated or trained and not free-willed and wild. All that compares to honey-hunters and their honeyguides is a relationship between fishermen and dolphins, documented as far back as first-century Rome, where dolphins blocked schools of fish from leaving ponds for the sea through narrow passes, forcing them into shallow water where men could catch them.

All in all, this study is huge news largely because it offers scientific evidence that a type of communication between humans and wild animals generally considered myth exists. “Our research only confirmed and quantified…what was already perfectly obvious to the honey-hunters,” Claire said. “Indigenous knowledge isn’t always right, but this is a relationship deeply embedded in their culture.” In a wilderness like the plains around Mbamba, according to Claire, this type of relationship may survive for a long time. The greatest hope now is that something as rare and beautiful as this can survive and not be forgotten as folklore in the years to come.

Copyright: pascalou95 / 123RF Stock Photo

.jpg)